Malayalis

Malayali men doing Kalaripayattu | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 40 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Kerala 32,413,213 Lakshadweep 54,267 Rest of India 2,371,339 | |

| Significant Malayali diaspora in | |

| 1,014,000[2] | |

| 745,000[3] | |

| 634,728[3] | |

| 595,000[2] | |

| 369,000[4] [better source needed] | |

| 300,000[5] [unreliable source?] | |

| 195,300[3] | |

| 101,556[3] | |

| 78,738[6][7][8][9] | |

| 77,910[10] | |

| 45,264[11] | |

| 26,000[12] | |

| 24,674[13] | |

| 9,024[14] | |

| 6,000[15] | |

| 25,000-45,000[16] | |

| 5,000 | |

| 5,000[17] | |

| 4,000[citation needed] | |

| 7,122 | |

| 3,785[18] | |

| 633[19] | |

| 500[20] | |

| Languages | |

| Malayalam | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Minority | |

| മലയാളം (Malayalam) | |

|---|---|

| Person | മലയാളി Malayāḷi |

| People | മലയാളികൾ Malayāḷikaḷ |

| Language | മലയാളം Malayāḷam |

| Country | കേരളം Kēraḷam |

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

The Malayali people (Malayalam: [mɐlɐjaːɭi]; also spelt Malayalee and sometimes known by the demonym Keralite) are a Dravidian ethnolinguistic group originating from the present-day state of Kerala & Union Territory of Lakshadweep in India, occupying its southwestern Malabar coast. They form the majority of the population in Kerala and Lakshadweep. They are predominantly native speakers of the Malayalam language, one of the eleven classical languages of India.[21] The state of Kerala was created in 1956 through the States Reorganisation Act. Prior to that, since the 1800s existed the Kingdom of Travancore, the Kingdom of Cochin, Malabar District, and South Canara of the British India. The Malabar District was annexed by the British through the Third Mysore War (1790–92) from Tipu Sultan. Before that, the Malabar District was under various kingdoms including the Zamorins of Calicut, Kingdom of Tanur, Arakkal kingdom, Kolathunadu, Valluvanad, and Palakkad Rajas.[22][23]

According to the Indian census of 2011, there are approximately 33 million Malayalis in Kerala,[24] making up 97% of the total population of the state. Malayali minorities are also found in the neighboring state of Tamil Nadu, mainly in Kanyakumari district and Nilgiri district and Dakshina Kannada and Kodagu districts of Karnataka and also in other metropolitan areas of India. Over the course of the later half of the 20th century, significant Malayali communities have emerged in Persian Gulf countries, including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar and Kuwait and to a lesser extent, other developed nations with a primarily immigrant background such as Malaysia, Singapore, the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, New Zealand and Canada. As of 2013, there were an estimated 1.6 million ethnic Malayali expatriates worldwide.[25] The estimated population of Malayalees in Malaysia in year 2020 is approximately 348,000, which makes up 12.5% of the total number of Indian population in Malaysia that makes them the second biggest Indian ethnic group in Malaysia, after the Tamils. Most of the Malayalee population in Malaysia aged 18 to 30 are known to be either the third, fourth, or fifth generation living as a Malaysian citizen. According to A. R. Raja Raja Varma, Malayalam was the name of the place, before it became the name of the language spoken by the people.[26]

Etymology

[edit]Malayalam, the native language of Malayalis, has its origin from the words mala meaning "mountain" and alam meaning "land" or "locality".[27] Kerala was usually known as Malabar in the foreign trade circles in the medieval era.[28] Earlier, the term Malabar had also been used to denote Tulu Nadu and Kanyakumari which lie contiguous to Kerala in the southwestern coast of India, in addition to the modern state of Kerala.[29][30] The people of Malabar were known as Malabars. Until the arrival of the East India Company, the term Malabar was used as a general name for Kerala, along with the term Kerala.[28] From the time of Cosmas Indicopleustes (6th century CE) itself, the Arab sailors used to call Kerala as Male. The first element of the name, however, is attested already in the Topography written by Cosmas Indicopleustes. This mentions a pepper emporium called Male, which clearly gave its name to Malabar ('the country of Male'). The name Male is thought to come from the Dravidian word Mala ('hill').[31][32] Al-Biruni (973–1048 CE) is the first known writer to call this country Malabar.[28] Authors such as Ibn Khordadbeh and Al-Baladhuri mention Malabar ports in their works.[33] The Arab writers had called this place Malibar, Manibar, Mulibar, and Munibar. Malabar is reminiscent of the word Malanad which means the land of hills.[34] According to William Logan, the word Malabar comes from a combination of the Dravidian word Mala (hill) and the Persian/Arabic word Barr (country/continent).[35] Hence the natives of Malabar Coast were known as Malabarese or Malabari in the foreign trade circles.[28][34] The words Malayali and Malabari are synonymous to each other.[28][34] The Skanda Purana mentions the ecclesiastical office of the Thachudaya Kaimal who is referred to as Manikkam Keralar (The Ruby King of Kerala), synonymous with the deity of the Koodalmanikyam temple.[36][37]

Geographic distribution and population

[edit]Malayalam is a language spoken by the native people of southwestern India (from Mangalore to Kanyakumari) and the islands of Lakshadweep in Arabian Sea. According to the Indian census of 2001, there were 30,803,747 speakers of Malayalam in Kerala, making up 93.2% of the total number of Malayalam speakers in India, and 96.7% of the total population of the state. There were a further 701,673 (2.1% of the total number) in Tamil Nadu, 557,705 (1.7%) in Karnataka and 406,358 (1.2%) in Maharashtra. The number of Malayalam speakers in Lakshadweep is 51,100, which is only 0.15% of the total number, but is as much as about 84% of the population of Lakshadweep. In all, Malayalis made up 3.22% of the total Indian population in 2001. Of the total 33,066,392 Malayalam speakers in India in 2001, 33,015,420 spoke the standard dialects, 19,643 spoke the Yerava dialect and 31,329 spoke non-standard regional variations like Eranadan.[24] As per the 1991 census data, 28.85% of all Malayalam speakers in India spoke a second language and 19.64% of the total knew three or more languages. Malayalam was the most spoken language in erstwhile Gudalur taluk (now Gudalur and Panthalur taluks) of Nilgiris district in Tamil Nadu which accounts for 48.8% population and it was the second most spoken language in Mangalore and Puttur taluks of South Canara accounting for 21.2% and 15.4% respectively according to 1951 census report.[38] 25.57% of the total population in the Kodagu district of Karnataka are Malayalis, in which Malayalis form the largest linguistic group in Virajpet Taluk.[39] Around one-third of the Malayalis in Kodagu district speak the Yerava dialect according to the 2011 census, which is native to Kodagu and Wayanad.[39] Around one-third of population in Kanyakumari district are also Malayalis. As of 2011 India census, Mahé district of Union Territory of Puducherry had a population of 41,816, predominantly Malayalis.

Just before independence, Malaya attracted many Malayalis. Large numbers of Malayalis have settled in Chennai (Madras), Delhi, Bangalore, Mangalore, Coimbatore, Hyderabad, Mumbai (Bombay), Ahmedabad and Chandigarh. Many Malayalis have also emigrated to the Middle East, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Europe. As of 2009–2013, there were approximately 146,000 people with Malayali heritage in the United States,[40] with an estimated 40,000 living in the New York tri-state area.[41] There were 7,093 Malayalam speakers in Australia in 2006.[7] The 2001 Canadian census reported 7,070 people who listed Malayalam as their mother tongue, mostly in the Greater Toronto Area and Southern Ontario. In 2010, the Census of Population of Singapore reported that there were 26,348 Malayalees in Singapore.[42] The 2006 New Zealand census reported 2,139 speakers.[43] 134 Malayalam speaking households were reported in 1956 in Fiji. There is also a considerable Malayali population in the Persian Gulf regions, especially in Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, UAE, Kuwait and European region mainly in London. The city of Chennai has the highest population of Malayalis in a metropolitan area outside Kerala, followed by Bangalore.

Besides, the Malayalee citizens in Malaysia are estimated to be 229,800 in the year 2020 whereas the population of the Malayalee expatriates is approximately 2,000. They make up around 10 percent of the total number of Indians in Malaysia.

History and culture

[edit]During the ancient period, the people of present-day Kerala were ruled by the Chera dynasty of Tamilakam, with their capital at Vanchi.[44]

The Malayalis live in a historic area known as the Malabar coast, which for thousands of years has been a major center of the international spice trade, operating at least from the Roman era with Ptolemy documenting it on his map of the world in 150 AD. For that reason, a highly distinct culture was created among the Malayali due to centuries of contact with foreign cultures through the spice trade. The arrival of the Cochin Jews, the rise of Saint Thomas Christians, and the growth of Mappila Muslim community, in particular, were very significant in shaping modern-day Malayali culture. Later, Portuguese Latin Christians, Dutch Malabar, French Mahe, and British English, which arrived after 1498 left their mark through colonialism and pillaging their resources.

In 2017, a detailed study of the evolution of the Singapore Malayalee community over a period of more than 100 years was published as a book: From Kerala to Singapore: Voices of the Singapore Malayalee Community. It is believed to be the first in-depth study of the presence of a NRI Malayalee community outside of Kerala.[45]

Language and literature

[edit]

Although disputed, the widely held view consider the Malayalam language to be descended from a dialect of early middle Tamil Language spoken on the Malabar coast, and largely arose because of its geographical isolation from the rest of the Tamil speaking areas. The Sangam literature can be considered as the ancient predecessor of Malayalam.[46] Malayalam literature is ancient in origin, and includes such figures as the 14th century Niranam poets (Madhava Panikkar, Sankara Panikkar and Rama Panikkar), whose works mark the dawn of both modern Malayalam language and indigenous Keralite poetry. Some linguists claim that an inscription found from Edakkal Caves, Wayanad, which belongs to 3rd century CE (approximately 1,800 years old), is the oldest available inscription in Malayalam, as they contain two modern Malayalam words, Ee (This) and Pazhama (Old), those are not found in literary Tamil. Although this has been disputed by scholars who regard it as a regional dialect of Old Tamil.[47] The use of the pronoun ī and the lack of the literary Tamil -ai ending are archaisms from Proto-Dravidian rather than unique innovations of Malayalam.[note 1] The origin of Malayalam calendar dates back to year 825 CE.[49][50][51] It is generally agreed that the Quilon Syrian copper plates of 849/850 CE is the available oldest inscription written in Old Malayalam. For the first 600 years of Malayalam calendar, the literature mainly consisted of the oral Ballads such as Vadakkan Pattukal (Northern Songs) in North Malabar and Thekkan Pattukal (Southern songs) in Southern Travancore.[46] The earliest known literary works in Malayalam are Ramacharitam and Thirunizhalmala, two epic poems written in Old Malayalam. Malayalam literature has been presented with 6 Jnanapith awards, the second-most for any Dravidian language and the third-highest for any Indian language.[52][53]

Designated a "Classical Language in India" in 2013,[21] it developed into the current form mainly by the influence of the poets Cherusseri Namboothiri (Born near Kannur),[54][55] Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan (Born near Tirur),[55] and Poonthanam Nambudiri (Born near Perinthalmanna),[55][56] in the 15th and the 16th centuries of Common Era.[55][57] Kunchan Nambiar, a Palakkad-based poet also influenced a lot in the growth of modern Malayalam literature in its pre-mature form, through a new literary branch called Thullal.[55] The prose literature, criticism, and Malayalam journalism, began following the latter half of 18th century CE. The first travelogue in any Indian language is the Malayalam Varthamanappusthakam, written by Paremmakkal Thoma Kathanar in 1785.[58][59]

The Triumvirate of poets (Kavithrayam: Kumaran Asan, Vallathol Narayana Menon and Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer)[60] are recognized for moving Keralite poetry away from archaic sophistry and metaphysics and towards a more lyrical mode. In 19th century Chavara Kuriakose Elias, the founder of Carmelites of Mary Immaculate and Congregation of Mother of Carmel congregations, contribute different streams in the Malayalam Literature. All his works are written between 1829 and 1870. Chavara's contribution[61] to Malayalam literature includes, Chronicles, Poems – athmanuthapam (compunction of the soul), Maranaveettil Paduvanulla Pana (Poem to sing in the bereaved house) and Anasthasiayude Rakthasakshyam – and other Literary works . Contemporary Malayalam literature deals with social, political, and economic life context. The tendency of the modern poetry is often towards political radicalism.[62] The writers like Kavalam Narayana Panicker have contributed much to Malayalam drama.[46] In the second half of the 20th century, Jnanpith winning poets and writers like G. Sankara Kurup, S. K. Pottekkatt, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, M. T. Vasudevan Nair, O. N. V. Kurup, and Akkitham Achuthan Namboothiri, had made valuable contributions to the modern Malayalam literature.[63][64][65][66][67] Later, writers like O. V. Vijayan, Kamaladas, M. Mukundan, Arundhati Roy, and Vaikom Muhammed Basheer, have gained international recognition.[68][69][70][71]

Arabi Malayalam (also called Mappila Malayalam[72][73] and Moplah Malayalam) was the traditional Dravidian language[74] of the Mappila Muslim community in Malabar Coast. The poets like Moyinkutty Vaidyar and Pulikkottil Hyder have made notable contributions to the Mappila songs, which is a genre of the Arabi Malayalam literature.[75][76] The Arabi Malayalam script, otherwise known as the Ponnani script,[77][78][79] is a writing system - a variant form of the Arabic script with special orthographic features - which was developed during the early medieval period and used to write Arabi Malayalam until the early 20th century CE.[80][81] Though the script originated and developed in Kerala, today it is predominantly used in Malaysia and Singapore by the migrant Muslim community.[82][83]

The modern Malayalam grammar is based on the book Kerala Panineeyam written by A. R. Raja Raja Varma in late 19th century CE.[84] World Malayali Council with its sister organisation, International Institute for Scientific and Academic Collaboration (IISAC) has come out with a comprehensive book on Kerala titled 'Introduction to Kerala Studies,’ specially intended for the Malayali diaspora across the globe. J.V. Vilanilam, former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Kerala; Sunny Luke, medical scientist and former professor of Medical Biotechnology at Adelphi University, New York; and Antony Palackal, professor of sociology at the Loyola College of Social Sciences in Thiruvananthapuram, have edited the book, besides making other contributions to it.

Tharavadu

[edit]Tharavad, also spelled as Tharavadu is the ancestral home of aristocratic families in Kerala, which usually served as the common house for the matrilineal joint family system practiced in the state.[85][86] Each Tharavadu has a unique name. The Tharavadu was administered by the Karanavar, the oldest male member of the family.[87] He would be the eldest maternal uncle of the family as well. The members of the Tharavadu consisted of mother, daughters, sons, sisters and brothers. The fathers and husbands had a very minimal role to play in the affairs of the Tharavadu. It was a true matrilineal affair. The Karanavar took all major decisions. He was usually autocratic. However, the consent of the eldest female member of the family was taken before implementing the decisions. This eldest female member would be his maternal grandmother, own mother, mother's sister, his own sister or a sister through his maternal lineage. Since the lineage was through the female members, the birth of a daughter was always welcomed. Each Tharavadu also has a Para Devatha (clan deity) revered by those in the particular Tharavadu. Temples were built to honour these deities.

Kerala's society is less patriarchal than the rest of India.[citation needed] Certain Hindu communities such as the Nairs, Muslims around Kannur, Some parts of Kozhikode district and Ponnani in Malappuram, and Varkala and Edava in Thiruvananthapuram used to follow a traditional matrilineal system known as marumakkathayam [88] which has in the recent years (post-Indian independence) ceased to exist. Christians, majority of the Muslims, Kerala's gender relations are among the most equitable in India and the Majority World.[citation needed]

Architecture

[edit]

Kerala, the ancestral land of the Malayali people, has a tropical climate with excessive rains and intensive solar radiation.[89] The architecture of this region has evolved to meet these climatic conditions by having the form of buildings with low walls, sloping roof and projecting caves.[89] The setting of the building in the open garden plot was again necessitated by the requirement of wind for giving comfort in the humid climate.[89]

Timber is the prime structural material abundantly available in many varieties in Kerala. Perhaps the skillful choice of timber, accurate joinery, artful assembly, and delicate carving of the woodwork for columns, walls and roofs frames are the unique characteristics of Malayali architecture.[89] From the limitations of the materials, a mixed-mode of construction was evolved in Malayali architecture. The stonework was restricted to the plinth even in important buildings such as temples. Laterite was used for walls. The roof structure in timber was covered with palm leaf thatching for most buildings and rarely with tiles for palaces or temples.[89] The Kerala murals' are paintings with vegetable dyes on wet walls in subdued shades of brown. The indigenous adoption of the available raw materials and their transformation as enduring media for architectural expression thus became the dominant feature of the Malayali style of architecture.[89]

Nalukettu

[edit]Nalukettu was a housing style in Kerala. Nalukettu is a quadrangular building constructed after following the Tachu Sastra (Science of Carpentry). It was a typical house that was flanked by out-houses and utility structures. The large house-Nalukettu is constructed within a large compound. It was called Nalukettu because it consisted of four wings around a central courtyard called Nadumuttom. The house has a quadrangle in the center. The quadrangle is in every way the center of life in the house and very useful for the performance of rituals. The layout of these homes was simple, and catered to the dwelling of numerous people, usually part of a tharavadu. Ettukettu (eight halls with two central courtyards) or Pathinarukettu (sixteen halls with four central courtyards) are the more elaborate forms of the same architecture.

An example of a Nalukettu structure is Mattancherry Palace.[90]

Performing arts and music

[edit]

Malayalis use two words to denote dance, which is attom and thullal.[91] The art forms of Malayalis are classified into three types: religious, such as Theyyam and Bhagavatipattu; semi religious, like Sanghakali and Krishnanattom; and secular, such as Kathakali, Mohiniyattam, and Thullal.[91] Kathakali and Mohiniyattam are the two classical dance forms from Kerala.[92] Kathakali is actually a dance-drama. Mohiniyattam is a very sensual and graceful dance form that is performed both solo and in a group by women.[92] Kutiyattam is a traditional performing art form from Kerala, which is recognised by UNESCO and given the status Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[93] Ottamthullal is another performing art, which is also known as the poor man's Kathakali, which was created by the poet Kunchan Nambiar as an alternative to Chakiarkooth (another performing art), which was open only for higher castes to see.[94] Theyyam is a ritualistic art form of Malayalis, which is thought to predate hinduism and to have developed from folk dances performed in conjunction with harvest celebrations. Theyyam is performed as an offering to gods so as to get rid of poverty and illness.[95] Velakali is another ritualistic art form, mainly performed at temples in the festival time. Kolkali is a folk art in which dance performers move in a circle, striking small sticks and keeping rhythm with special steps.

Many ancient Malayali family houses in Kerala have special snake shrines called Kavu. Sarpam Thullal is usually performed in the courtyard of houses having snake shrines. This is a votive offering for family wealth and happiness. Kerala Natanam (കേരള നടനം) (Kerala Dance) is a new style of dance that is now recognized as a distinct classical art form evolved from Kathakali. The Indian dancer Guru Gopinath (ഗുരു ഗോപിനാഥ്) a well-trained Kathakali artist and his wife Thankamani Gopinath developed this unique form of dance.

Performing arts in Kerala is not limited to a single religion of the Malayali society. Muslim Mappilas, Nasranis Mappilas and Latin Christians have their own unique performing art forms. Duff Muttu, also known as Dubh Muttu/Aravanamuttu[96] is a performing art form prevalent among the Muslim community. It is a group performance, staged as a social event during festivals and nuptial ceremonies.[96]

Oppana is a popular form of social entertainment among the Muslim community. It is a form accompanied by clapping of hands, in which both men and women participate.[citation needed]

Margamkali is a performing art which is popular among the Nasrani Mappilas. It combines both devotion and entertainment, and was performed by men in groups.[97] Since 1980's women also have found groups. The dancers themselves sing the margamkali songs in unison call and response form.[97] Parichamuttukali is another performing art which is popular among Nasranis. This is an artistic adaptation of the martial art of Kerala, Kalaripayattu.[97] Chavittu nadakom is a theatrical art form observed mainly by Kerala Latin Christians, dating back to the second half of the 16th century.[97]

However, many of these native art forms largely play to tourists or at youth festivals, and are not as popular among ordinary Keralites. Thus, more contemporary forms – including those heavily based on the use of often risqué and politically incorrect mimicry and parody – have gained considerable mass appeal in recent years. Indeed, contemporary artists often use such modes to mock socioeconomic elites. Since 1930 when the first Malayalam film Vigathakumaran was released and over the following decade or two, Malayalam Cinema had grown to become one of the popular means of expression for both works of fiction and social issues, and it remains so.

Music formed a major part of early Malayalam literature, which is believed to have started developing by 9th century CE.[98] The significance of music in the culture of Kerala can be established just by the fact that in Malayalam language, musical poetry was developed long before prose. Kerala is musically known for Sopanam. Sopanam is religious in nature, and developed through singing invocatory songs at the Kalam of Kali, and later inside temples. Sopanam came to prominence in the wake of the increasing popularity of Jayadeva's Gita Govinda or Ashtapadis. Sopana sangeetham (music), as the very name suggests, is sung by the side of the holy steps (sopanam) leading to the sanctum sanctorum of a shrine. It is sung, typically employing plain notes, to the accompaniment of the small, hourglass-shaped ethnic drum called idakka, besides the chengila or the handy metallic gong to sound the beats.

Sopanam is traditionally sung by men of the Maarar and Pothuval community, who are Ambalavasi (semi-Brahmin) castes engaged to do it as their hereditary profession. Kerala is also home of Carnatic music. Legends like Swati Tirunal, Shadkala Govinda Maarar, Sangitha Vidwan Gopala Pillai Bhagavathar, Chertala Gopalan Nair, M. D. Ramanathan, T.V.Gopalakrishnan, M.S. Gopalakrishnan, L. Subramaniam T.N. Krishnan & K. J. Yesudas are Malayali musicians. Also among the younger generations with wide acclaim and promise is Child Prodigy Violinist L. Athira Krishna etc., who are looked upon as maestros of tomorrow.[99]

Kerala also has a significant presence of Hindustani music as well.[100] The king of Travancore, Swathi Thirunal patronaged and contributed much to the Hindustani Music. The pulluvar of Kerala are closely connected to the serpent worship. One group among these people consider the snake gods as their presiding deity and performs certain sacrifices and sing songs. This is called Pulluvan Pattu. The song conducted by the pulluvar in serpent temples and snake groves is called Sarppapaattu, Naagam Paattu, Sarpam Thullal, Sarppolsavam, Paambum Thullal or Paambum Kalam. Mappila Paattukal or Mappila Songs are folklore Muslim devotional songs in the Malayalam language. Mappila songs are composed in colloquial Malayalam and are sung in a distinctive tune. They are composed in a mixture of Malayalam and Arabic.

Film music, which refers to playback singing in the context of Indian music, forms the most important canon of popular music in India. Film music of Kerala in particular is the most popular form of music in the state.[100]

Vallam Kali

[edit]

Vallam Kali is the race of country-made boats. It is mainly conducted during the season of the harvest festival Onam in Autumn. Vallam Kali include races of many kinds of traditional boats of Kerala. The race of Chundan Vallam (snake boat) is the major item. Hence Vallam Kali is also known in English as Snake Boat Race and a major tourist attraction. Other types of boats which do participate in various events in the race are Churulan Vallam, Iruttukuthy Vallam, Odi Vallam, Veppu Vallam (Vaipu Vallam), Vadakkanody Vallam, and Kochu Vallam. Nehru Trophy Boat Race is one of the famous Vallam Kali held in Punnamada Lake in Alappuzha district of Kerala. Champakulam Moolam Boat Race is the oldest and most popular Vallam Kali in Kerala. The race is held on river Pamba on the moolam day (according to the Malayalam Era) of the Malayalam month Midhunam, the day of the installation of the deity at the Ambalappuzha Sree Krishna Temple. The Aranmula Boat Race takes place at Aranmula, near a temple dedicated to Lord Krishna and Arjuna. The President's Trophy Boat Race is a popular event conducted in Ashtamudi Lake in Kollam.

Thousands of people gather on the banks of the river Pamba to watch the snake boat races. Nearly 50 snake boats or chundan vallams participate in the festival. Payippad Jalotsavam is a three-day water festival. It is conducted in Payippad Lake which is 35 km from Alappuzha district of Kerala state. There is a close relation between this Payippad boat race and Subramanya Swamy Temple in Haripad. Indira Gandhi Boat Race is a boat race festival celebrated in the last week of December in the backwaters of Kochi, a city in Kerala. This boat race is one of the most popular Vallam Kali in Kerala. This festival is conducted to promote Kerala tourism.

Festivals

[edit]

Malayalis celebrate a variety of festivals, namely Onam, Vishu, Deepavali, and Christmas.

Cuisine

[edit]

Malayali cuisine is not homogeneous and regional variations are visible throughout. Spices form an important ingredient in almost all curries. Kerala is known for its traditional sadhyas, a vegetarian meal served with boiled rice and a host of side-dishes. The sadhya is complemented by payasam, a sweet milk dessert native to Kerala. The sadhya is, as per custom, served on a banana leaf. Traditional dishes include sambar, aviyal, kaalan, theeyal, thoran, injipully, pulisherry, appam, kappa (tapioca), puttu (steamed rice powder), and puzhukku. Coconut is an essential ingredient in most of the food items and is liberally used.[101]

Puttu is a culinary specialty in Kerala. It is a steamed rice cake which is a favorite breakfast of most Malayalis. It is served with either brown chickpeas cooked in a spicy gravy, papadams and boiled small green lentils, or tiny ripe yellow Kerala plantains. In the highlands there is also a variety of puttu served with paani (the boiled-down syrup from sweet palm toddy) and sweet boiled bananas. to steam the puttu, there is a special utensil called a puttu kutti. It consists of two sections. The lower bulkier portion is where the water for steaming is stored. The upper detachable leaner portion is separated from the lower portion by perforated lids so as to allow the steam to pass through and bake the rice powder.[102]

Appam is a pancake made of fermented batter. The batter is made of rice flour and fermented using either yeast or toddy, the local spirit. It is fried using a special frying pan called appa-chatti and is served with egg curry, chicken curry, mutton stew, vegetable curry and chickpea curry.[103]

Muslim cuisine or Mappila cuisine is a blend of traditional Kerala, Persian, Yemenese and Arab food culture.[104] This confluence of culinary cultures is best seen in the preparation of most dishes.[104] Kallummakkaya (mussels) curry, Irachi Puttu (Irachi means meat), parottas (soft flatbread),[104] Pathiri (a type of rice pancake)[104] and ghee rice are some of the other specialties. The characteristic use of spices is the hallmark of Mappila cuisine. spices like black pepper, cardamom and clove are used profusely. The Kerala Biryani, is also prepared by the community.[105]

The snacks include Unnakkaya (deep-fried, boiled ripe banana paste covering a mixture of cashew, raisins and sugar),[106] pazham nirachathu (ripe banana filled with coconut grating, molasses or sugar),[106] Muttamala made of eggs,[104] Chattipathiri, a dessert made of flour, like baked, layered Chapatis with rich filling, Arikkadukka and so on.[104]

Martial arts

[edit]

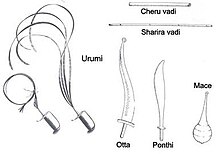

Malayalis have their own form of martial arts called Kalaripayattu. This type of martial arts was used as a defensive mechanism against intruders. In ancient times, disputes between nobles (naaduvazhis or Vazhunors) were also settled by the outcome of a Kalaripayattu tournament. This ancient martial art is claimed as the mother of all martial arts. The word "kalari" can be traced to ancient Sangam literature.[107]

Anthropologists estimate that Kalarippayattu dates back to at least the 12th century CE.[108] The historian Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai attributes the birth of Kalaripayattu to an extended period of warfare between the Cheras and the Cholas in the 11th century CE.[108] What eventually crystallized into this style is thought to have been a product of existing South Indian styles of combat, combined with techniques brought by other cultures.[108] Kalaripayattu may be one of the oldest martial arts in existence.[109] The oldest western reference to Kalaripayattu is a 16th-century travelogue of Duarte Barbosa, a Portuguese explorer. The southern style, which stresses the importance of hand-to-hand combat, is slightly different than Kalari in the north.[110]

See also

[edit]- Malabars

- Non Resident Keralites Affairs

- Kerala Gulf diaspora

- Ethnic groups in Kerala

- Malaysian Malayali

- Migrant labourers in Kerala

- Malayali Australian

- Garshom International Awards

- Malayalam movie

- Malayalam literature

- Malayalam script

- Malayali cartoonists

Notes

[edit]- ^ "*aH and *iH are demonstrative adjectives reconstructed for Proto-Dravidian, as they show variation in vowel length. When they occur in isolation they occur as ā, and ī but when they are followed by a consonant initial word then they appear as a- and i- as in Ta. appoẓutu 'that time'., : Te. appuḍu id. and Ta. ippoẓutu 'that time'., : Te.ippuḍu id. However, Modern Tamil has replaced ā, and ī with anda and inda but most Dravidian languages have preserved it."[48][page needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Census of India" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Kerala Migration Survey - 2014". The Indian Express. (This is the number of approximate emigrants from Kerala, which is closely related to, but different from the actual number of Malayalis.). No. 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Zachariah, K. C. & Rajan, S. Irudaya (2011), Kerala Migration Survey 2011 Archived 10 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Department of Non-resident Keralite Affairs, Government of Kerala, p. 29. This is the number of emigrants from Kerala, which is closely related to but different from the actual number of Malayalis /Malayalees.

- ^ "Malayali, Malayalam in Malaysia". Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "FOKANA, About Us". Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "SBS Census Explorer: How diverse is your community?". Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b "The People of Australia: Statistics from the 2011 Census" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "In the Australia, 18% of people spoke a language other than English at home in 2011". abs.gov.au/. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "India-born Malayalam-speaking community in Australia: Some interesting trends". The Times of India. No. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (17 August 2022). "Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ "Survey finds only 16.25 lakh NoRKs". The Hindu. 31 October 2013. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Singapore Malayalee Association 100th Anniversary". 27 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ "Irish Census 2022". Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "2018 Census Totals by Topic – National Highlights (Updated)". Statistics New Zealand. 30 April 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Where Malayalees once held sway". DNA India. 5 October 2005. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Muringatheri, Mini (22 September 2023). "Learning German made easy for Keralites". The Hindu.

- ^ "With Kerala in their hearts..." Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ "Vienna Malayalee Association". Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Väestö 31.12. Muuttujina Maakunta, Kieli, Ikä, Sukupuoli, Vuosi ja Tiedot". Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Welcome to Nionkairali.com - Indian Malayalees in Japan- Japan malayalees, Malayali, Keralite, Tokyo". nihonkairali.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b "'Classical' status for Malayalam". The Hindu. Thiruvananthapuram, India. 24 May 2013. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "Travancore." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2011. Web. 11 November 2011.

- ^ Chandra Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life in Colonial South India, 1863–1937: Contending with Marginality, RoutledgeCurzon, 2004, p. 30

- ^ a b http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/Census_Data_Online/Language/data_on_language.html Archived 10 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, censusindia.net

- ^ 재외동포현황 총계(2015)/Total number of overseas Koreans (2015). South Korea: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Varma, A.R. Rajaraja (2005). Keralapanineeyam. Kottayam: D C Books. ISBN 81-7130-672-1.

- ^ "kerala.gov.in". Archived from the original on 18 January 2006. – go to the website and click the link – language & literature to retrieve the information

- ^ a b c d e Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-264-1588-5. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ J. Sturrock (1894). "Madras District Manuals - South Canara (Volume-I)". Madras Government Press.

- ^ V. Nagam Aiya (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press.

- ^ C. A. Innes and F. B. Evans, Malabar and Anjengo, volume 1, Madras District Gazetteers (Madras: Government Press, 1915), p. 2.

- ^ M. T. Narayanan, Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar (New Delhi: Northern Book Centre, 2003), xvi–xvii.

- ^ Mohammad, K.M. "Arab relations with Malabar Coast from 9th to 16th centuries" Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol. 60 (1999), pp. 226–34.

- ^ a b c Malabar Manual (1887), William Logan, Calicut

- ^ Logan, William (1887). Malabar Manual, Vol. 1. Servants of Knowledge. Superintendent, Government Press (Madras). p. 1. ISBN 978-81-206-0446-9.

- ^ See Sahyadri Kanda Chapter 7 in Skanda Purana. Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447025225.

- ^ Who's Who in Madras 1934

- ^ "South Kanara, The Nilgiris, Malabar and Coimbators Districts". Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Census of India - Language". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009-2013". Census.gov. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Keralite Indians in the New York Metro Area" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2023.

- ^ Pillai, Anitha Devi (2017). From Kerala to Singapore : Voices from the Singapore Malayalee community. Puva Arumugam. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Pte Ltd. ISBN 9789814721837. OCLC 962741080.

- ^ Statistics New Zealand:Language spoken (total responses) for the 1996–2006 censuses (Table 16) Archived 9 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, stats.govt.nz

- ^ Vimala, Angelina (2007). History and Civics. Pearson Education India. p. 107. ISBN 978-81-317-0336-6.

- ^ Pillai, Anitha Devi (2017). From Kerala to Singapore : voices from the Singapore Malayalee community. Puva Arumugam. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9789814721837. OCLC 962741080.

- ^ a b c Mathrubhumi Yearbook Plus - 2019 (Malayalam ed.). Kozhikode: P. V. Chandran, Managing Editor, Mathrubhumi Printing & Publishing Company Limited, Kozhikode. 2018. p. 453. ASIN 8182676444.

- ^ Sasibhooshan, Gayathri (12 July 2012). "Historians contest antiquity of Edakkal inscriptions". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43533-8. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Kollam Era" (PDF). Indian Journal History of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Broughton Richmond (1956), Time measurement and calendar construction, p. 218, archived from the original on 24 August 2023, retrieved 9 June 2021

- ^ R. Leela Devi (1986). History of Kerala. Vidyarthi Mithram Press & Book Depot. p. 408. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Naha, Abdul Latheef (24 September 2020). "Jnanpith given to Akkitham". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ ANI (29 November 2019). "Celebrated Malayalam poet Akkitham wins 2019 Jnanpith Award". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Dr. K. Ayyappa Panicker (2006). A Short History of Malayalam Literature. Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Information and Public Relations, Kerala.

- ^ Arun Narayanan (25 October 2018). "The Charms of Poonthanam Illam". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Freeman, Rich (2003). "Genre and Society: The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala". In Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia

- ^ Menon, A. Sreedhara (2008). The legacy of Kerala (1st DCB ed.). Kottayam, Kerala: D C Books. ISBN 978-81-264-2157-2.

- ^ "August 23, 2010 Archives". Archived from the original on 27 April 2013.

- ^ Natarajan, Nalini; Nelson, Emmanuel Sampath (18 December 1996). Handbook of Twentieth-century Literatures of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313287787. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Contents of Bl. Chavara". Christ University Library catalog. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014.

- ^ "South Asian arts". Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Subodh Kapoor (2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia: Biographical, Historical, Religious, Administrative, Ethnological, Commercial and Scientific. Mahi-Mewat. Cosmo. p. 4542. ISBN 978-8177552720. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Accessions List, South Asia. E.G. Smith for the U.S. Library of Congress Office, New Delhi. 1994. p. 21. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Indian Writing Today. Nirmala Sadanand Publishers. 1967. p. 21. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Amaresh Datta; Sahitya Akademi (1987). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: K to Navalram. Sahitya Akademi. p. 2394. ISBN 978-0836424232. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Malayalam Literary Survey. Kerala Sahitya Akademi. 1993. p. 19. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Eṃ Mukundan; C. Gopinathan Pillai (2004). Eng Adityan Radha And Others. Sahitya Akademi. p. 3. ISBN 978-8126018833. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Ed. Vinod Kumar Maheshwari (2002). Perspectives On Indian English Literature. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 126. ISBN 978-8126900930. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Amit Chaudhuri (2008). Clearing a Space: Reflections On India, Literature, and Culture. Peter Lang. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1906165017. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (15 October 1997). "Indian's First Novel Wins Booker Prize in Britain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ Kottaparamban, Musadhique (1 October 2019). "Sea, community and language: a study on the origin and development of Arabi- Malayalam language of mappila muslims of Malabar". Muallim Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities: 406–416. doi:10.33306/mjssh/31. ISSN 2590-3691. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Kuzhiyan, Muneer Aram. Poetics of Piety Devoting and Self Fashioning in the Mappila Literary Culture of South India (PhD). The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. hdl:10603/213506. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Kottaparamban, Musadhique (2 October 2019). "Sea, Community and Language: A Study on the Origin and Development of Arabi- Malayalam Language of Mappila Muslims of Malabar". Muallim Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities: 406–416. doi:10.33306/mjssh/31. ISSN 2590-3691. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Mappila songs cultural fountains of a bygone age, says MT". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 31 March 2007. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ Pg 167, Mappila Muslims: a study on society and anti colonial struggles By Husain Raṇdathaṇi, Other Books, Kozhikode 2007

- ^ Kunnath, Ammad (15 September 2015). The rise and growth of Ponnani from 1498 AD To 1792 AD (PhD). University of Calicut. hdl:10603/49524. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Panakkal, Abbas (2016). Islam in Malabar (1460-1600) : a socio-cultural study /. Kulliyyah Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Kallen, hussain Randathani. "Trade and culture: Indian ocean interaction on the coast of Malabar in medieval period". Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Miller, Roland. E., "Mappila" in "The Encyclopedia of Islam". Volume VI. E. J. Brill, Leiden. 1987. pp. 458-56.

- ^ Malayalam Resource Centre

- ^ Menon. T. Madhava. "A Handbook of Kerala, Volume 2", International School of Dravidian Linguistics, 2002. pp. 491-493.

- ^ "National Virtual Translation Center - Arabic script for Malayalam". Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Mathrubhumi Yearbook Plus - 2019 (Malayalam ed.). Kozhikode: P. V. Chandran, Managing Editor, Mathrubhumi Printing & Publishing Company Limited, Kozhikode. 2018. p. 454. ASIN 8182676444.

- ^ Kakkat, Thulasi (18 August 2012). "Kerala's Nalukettus". The Hindu. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Kunhikrishnan, K. (12 April 2003). "Fallen tharavads". The Hindu. Retrieved 13 December 2017.[dead link]

- ^ Osella, Filippo; Caroline, Filippo; Osella, Caroline (20 December 2000). Social Mobility in Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745316932. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mohamed Koya, S.M, MATRILINY AND MALABAR MUSLIMS, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 40 (1979), pp. 419-431 (13 pages)

- ^ a b c d e f "Kerala architecture". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ "Nalukettu". Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.-Malayalam Resource Centre

- ^ a b Sciences, International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological (18 December 1980). "The Communication of Ideas". Concept Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Classical Dances of India - Indian Classical Dances, Indian Dances, Dances of India". dances.indobase.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ Varghese, Theresa (18 December 2006). Stark World Kerala. Stark World Pub. ISBN 9788190250511. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Reciting: Webster's Quotations, Facts and Phrases. Icon Group International, Incorporated. 19 December 2008. ISBN 9780546721676. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Singh, Sarina (18 December 2005). India. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 9781740596947. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b India, Motilal (UK) Books of (18 February 2008). Tourist Guide to Kerala. Sura Books. ISBN 9788174781642 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Nettl, Bruno; Arnold, Alison; Stone, Ruth M.; Porter, James; Rice, Timothy; Olsen, Dale Alan; Miller, Terry E.; Kaeppler, Adrienne Lois; Sheehy, Daniel Edward; Koskoff, Ellen; Williams, Sean; Love, Jacob Wainwright; Goertzen, Chris; Danielson, Virginia; Marcus, Scott Lloyd; Reynolds, Dwight; Provine, Robert C.; Tokumaru, Yoshihiko; Witzleben, John Lawrence (18 December 1998). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia : the Indian subcontinent. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824049461. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sreedhara Menon, A. Kerala Charithram. Kottayam, Kerala: D.C. Books. p. 494.

- ^ Rolf, Killius (2006). Ritual Music and Hindu Rituals of Kerala. New Delhi: BR Rhythms. ISBN 81-88827-07-X.

- ^ a b "Music". Keral.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ "Onam Sadhya: 13 Dishes You Need To Try!". outlookindia.com/outlooktraveller/.

- ^ "Kerala's Favourite Breakfast: How to Make Soft Puttu at Home". NDTV Food. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Upadhye, Aishwarya (16 November 2018). "Appams anyone?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Sabhnani, Dhara Vora (14 June 2019). "Straight from the Malabar Coast". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Kerala biryani (With vegetables)". 22 April 2013. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ a b Kurian, Shijo (2 July 2014). "Flavours unlimited from the Malabar coast". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Suresh, P. R. (2005). Kalari Payatte – The martial art of Kerala. Archived 29 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Zarrilli, Phillip B. A South Indian Martial Art and the Yoga and Ayurvedic Paradigms. Archived 16 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- ^ "Discovery Latinoamérica". Archived from the original on 21 December 2009.

- ^ Phillip B. Zarrilli, When the Body Becomes All Eyes

Further reading

[edit]- Dr. K. Ayyappa Panicker (2006). A Short History of Malayalam Literature. Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Information and Public Relations, Kerala.

- Menon, A. Sreedhara (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786.

- Mathrubhumi Yearbook Plus - 2019 (Malayalam ed.). Kozhikode: P. V. Chandran, Managing Editor, Mathrubhumi Printing & Publishing Company Limited, Kozhikode. 2018.